By Pudge Kleinkauf

The following is an excerpt from the book “Rookie No More: The Fly Fishing Novice Gets Guidance From A Pro”

Question: How do I achieve the “dead drift” when I’m dry fly fishing?

Answer: Most fly anglers find that fishing dry flies on the surface of the water is one of their favorite ways to fish. Seeing a fish rise up from beneath the water to take our bug imitation is a very exciting part of our sport. Called dry fly fishing, it isn’t one of the easiest of skills to master, however. Achieving the dead drift results from two things: good casting and correct management of the fly on the water.

Dry fly fishing is often referred to as “fooling fish with fur and feathers.” A good imitation of the fish’s food source, placed on the water with an appropriate cast, should result in a fly that looks and drifts on the water like the real thing. That could be an adult mayfly, caddis, or stonefly returning to the water’s surface to lay its eggs, or a bee or ant blown into the water from stream-side vegetation.

While learning to fish dry flies, you need to start by being able to track the fly on the water. Use a very visible fly a size or two larger than you need or a small fly with a bit of white or colored calf tail or poly yarn on its top to provide a focal spot for your eye to key on. Two of the best flies to use while learning to dry-fly fish are the Parachute Adams and the Royal Wulff (tied with white calf-tail wings) in a size #12.

While learning to fish dry flies, you need to start by being able to track the fly on the water. Use a very visible fly a size or two larger than you need or a small fly with a bit of white or colored calf tail or poly yarn on its top to provide a focal spot for your eye to key on. Two of the best flies to use while learning to dry-fly fish are the Parachute Adams and the Royal Wulff (tied with white calf-tail wings) in a size #12.

“Find the fly on the surface just as soon as it lands,” I tell my students and clients, “and then never take your eyes off of it as it drifts along.” I also have beginners cast in fairly close to themselves until they train their eye to quickly locate the fly on the water at the end of the leader. As they become better able to judge distance, I have them extend their cast a little farther each time to learn how to spot the fly at greater distances. If you can’t follow your fly on the water, you won’t know how it is drifting.

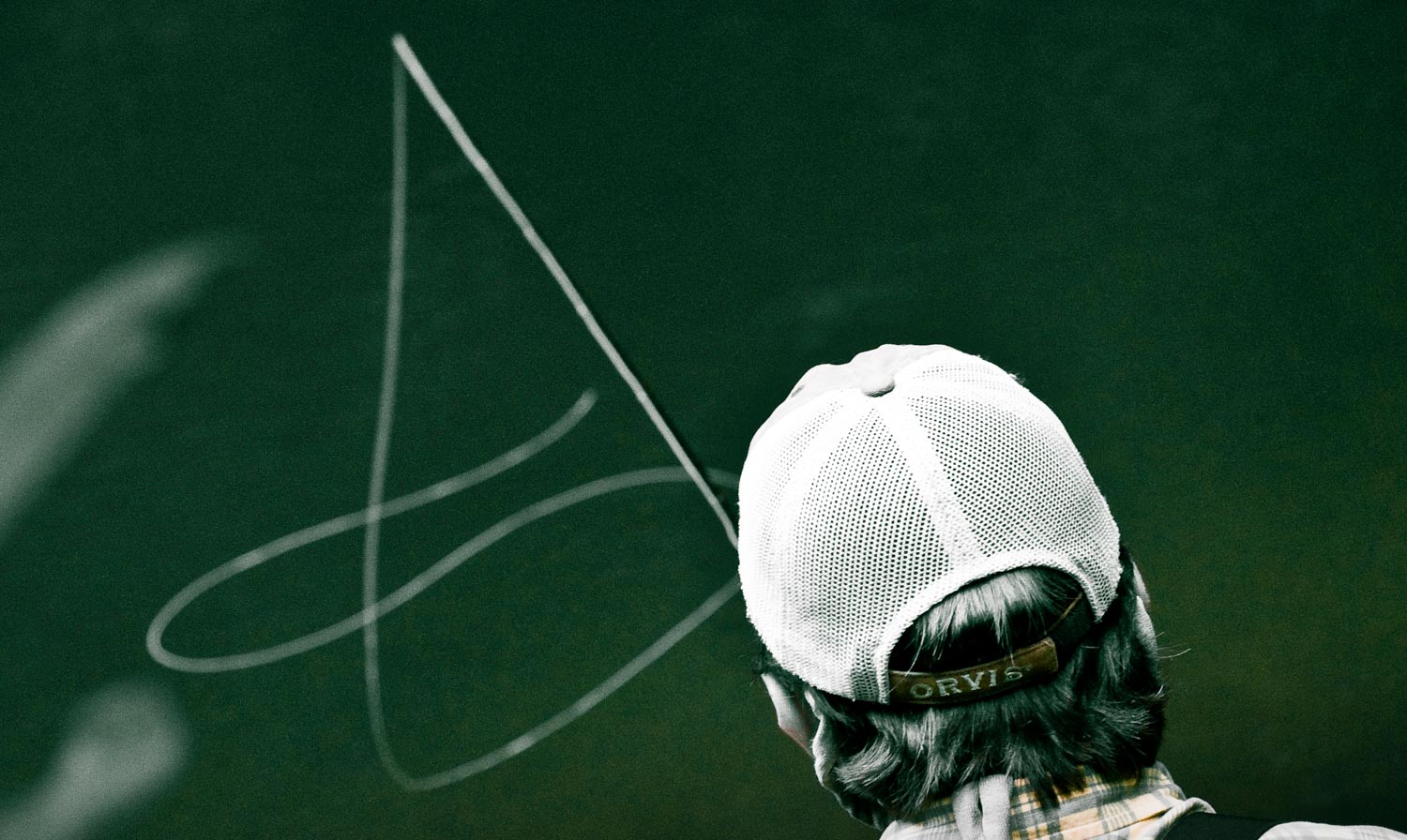

A well-executed overhead cast is the best cast to help achieve the delicacy and gentleness of a wispy, weightless, imitation bug descending and landing on the water. The fly must land silently, delicately, and naturally. My instructor repeated over and over, “Think flutter, Pudge. The fly should ‘flutter’ to the surface, not slap down on it.” Because I could clearly see the difference between a flutter and a splat, that image worked for me.

Fluttering results from a definitive stop of the rod at the eleven o’clock position (just at the end of the brim on a baseball cap) when you’re ready to deliver the fly. That stop permits the leader to propel the fly outward, aimed at a target two feet above the surface of the water. Unless you drop the rod tip too quickly, the fly will then drop gracefully from that target in the air down to the target on the water.

Fluttering results from a definitive stop of the rod at the eleven o’clock position (just at the end of the brim on a baseball cap) when you’re ready to deliver the fly. That stop permits the leader to propel the fly outward, aimed at a target two feet above the surface of the water. Unless you drop the rod tip too quickly, the fly will then drop gracefully from that target in the air down to the target on the water.

Causes of splats or placement of all of the fly line & leader on the water result from:

- Failure to stop the rod at the correct place;

- Failure to wait a few seconds for the leader to unfurl;

- Failure to keep the thumb in a more upright position so the wrist does not bend

- Failure to keep your arm from following through too soon after the stop.

All of these slipups make the line, and usually all of the leader, fall onto the surface of the water with a splat. Fish can both see and hear all this disturbance, and will quickly depart. Try using your phone to video yourself casting to see if you are stopping correctly to achieve flutter rather than splat.

Getting the fly to flutter to the water takes practice, but it is not the only essential part of offering the fly to the fish. Accuracy is another part of proper

presentation that needs to be perfected. It isn’t enough to just keep your fly from landing with a splat, it must also fall in the place where you intend so that it can drift to where you think the fish are waiting. Judging distance in relation to the current and estimating the amount of line and leader necessary to place the fly in the desired location are learned skills. They come with experience, awareness of how those skills must be applied in real life on real water, and, of course, with practice, practice, practice. Happily, that means that you must actually go fishing.

Once on the water, the fly must now drift naturally. The phrase used to describe that is dead drift, which means that the fly must float along as naturally as the real bug would. If it does not, we say that the fly is “dragging.”

Simply put, drag exists when the line and/or the leader pull the fly tight and prevent it from drifting freely and naturally on the water. If you pay close attention, it is pretty easy to spot a dragging fly in the water because it creates a “V-wake” in the water behind or beside itself. The fish know that the real bug doesn’t usually create drag in the water and will seldom take a dragging fly.

If the line and leader fully extend as you place the fly on the water, the fly will begin to pull against the leader almost immediately and drag sets in. To help avoid that scenario stop the rod tip high to achieve flutter, then wait to let the line and leader roll out and allow the fly to fall towards the water as naturally as possible.

Pudge Kleinkauf Gink & Gasoline www.ginkandgasoline.com hookups@ginkandgasoline.com Sign Up For Our Weekly Newsletter!Get your copy of “Rookie No More: The Fly Fishing Novice Gets Guidance From A Pro” HERE

Cecilia “Pudge” Kleinkauf teaches, writes and guides in Alaska. Her books include:

Cecilia “Pudge” Kleinkauf teaches, writes and guides in Alaska. Her books include:

–Rookie No More: The Fly Fishing Novice Gets Guidance from a Pro, Epicenter Press 2016

-Pacific Salmon Flies: New Ties & Old Standbys, Frank Amato Publications, 2012

–Fly Fishing for Alaska’s Arctic Grayling: Sailfish of the North, Frank Amato Publications, 2009

Benjamin Franklin Award-winning Books

–River Girls: Fly Fishing for Young Women, Johnson Books, 2006

-Fly Fishing Women Explore Alaska, Epicenter Press, 2003

Achieving a dead drift with a dry fly was one of hardest techniques for me to get good at. It seemed so easy to mend with an indicator, but doing the same thing with a dry would cause it to lift off and fly somewhere else. Finally convincing myself that mending for indicator fishing and mending for dries are two completely different techniques is what it took to finally achieve a good dry drift.