So you bought a switch rod…now what?

The idea behind the switch rod is simple. What if you could have the best of both worlds? What if you were nymphing under an indicator but you had the length of a Spey rod to highstick? What if you could cast a dry fly eighty feet without a backcast? What if you could swing flies on a skagit head and sink tip in the morning and dead drift dries in the afternoon without going back to the truck for another rod? Is that a world you’d like to fish in?

Switch rods are a wonderful and versatile tool for fly anglers but they can be as vexing as versatile. In fact, it is their versatility that makes them so confusing. There are about a dozen ways you can set up and fish that new switch rod. They range from nymphing for trout to swinging for steelhead and even casting in the surf for stripers. How your rod will fish starts with the line you choose and it all adds up to make selecting a line for your switch rod the most confusing choice in fly fishing.

I know a lot of guys come to the switch rod from a single-hand casting background. They hear all the talk about two-handed casting and get to feel like they are missing something. The switch rod offers the option of single-hand performance and seems like a friendly way into the world of two-handed casting. The trouble is that lots of those guys never get comfortable putting their left hand on the rod, usually because they don’t have the right line.

My experience was just the opposite. I was turned onto switch rods by my buddy Jeff Hickman while steelheading in the northwest. I was totally comfortable with two-hand casting with both Scandi and Skagit heads on the switch rod but when I got home to the southeast and wanted to try nymphing with my switch rod I found the set up challenging.

I started researching line choices and experienced option paralysis. “Holy Hell,” I thought, “How are you ever supposed to choose?” I’m lucky to have a friend who is a great two-hand caster and a line designer so I reached out to my buddy Simon Gawesworth at RIO for some help in making sense of it all. Simon’s response was invaluable and I will include it, but first, let’s talk a bit about the difference between traditional fly lines and Spey systems.

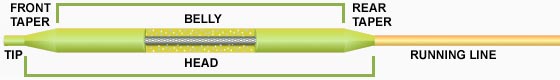

A traditional fly line, like the weight-forward line diagramed, has five parts. The front taper, the belly and the rear taper form the head. On the front end is the tip and on the back the running line. It’s a finely tuned system and each part serves a purpose.

The belly of the line works the hardest. It is responsible for loading the rod and carrying the weight of the fly. A light line like a 3-weight is balanced to load a light, soft rod. Its light belly lands softly on the water for a delicate presentation but it only has enough inertia to carry a light fly effectively. A 7-weight line, on the other hand, has a heavy belly that loads a heavy rod and will carry a big streamer, but it lacks delicacy.

The front taper is responsible for dissipating the energy of the belly and translating it to the leader. The front taper determines how the line turns over the leader and the fly. Many saltwater lines, for example, have short front tapers that deliver a lot of power to the leader. These lines turn over a long leader and big fly into the wind but it’s a skill to make a delicate presentation. A long front taper, on the other hand, dissipates more energy and will land a dry fly like a feather.

The rear taper, when the cast is long enough for it to be in play, translates energy from the rod to the belly. A long rear taper offers the caster more control over the belly while making a long cast. It is easier to make a smooth graceful loop with a long rear taper, when carrying a lot of line. A short rear taper, like the ones found in shooting head lines, are great for distance because they have less wind and guide resistance but they are hard to control.

These three parts that make up the head really determine how the line will cast. The tip and running line have the simpler tasks of connecting the head to the leader and backing. They are important but their purpose is more intuitive. There are limitless options and variations for any imaginable fishing situation. You choose the line that suits your needs.

Now let’s look at how that compares to a Spey system.

Spey lines are intimidating to the uninitiated with their many parts, options and loop to loop connections but there’s no need for alarm. Spey lines, in both form and function, are much the same as traditional fly lines. Think of them as traditional lines that have been cut into sections with scissors. What their design offers to the Spey caster is instant flexibility on the river. In a Spey system the running line, the head and sometimes the tip are separate. They serve all the same functions as their counterparts in traditional lines but the caster is free to choose from interchangeable heads and tips to meet his or her immediate needs. The direct connection of the head to the running line, more or less without a rear taper, is mute as there is no running line being carried in Spey casting.

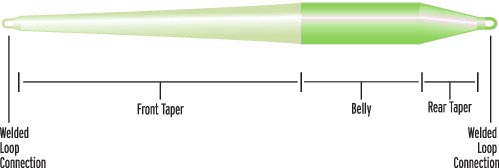

Let’s look at a Scandinavian or Scandi head. A Scandi head has a long graceful front taper, generally a short belly with most of the weight in the rear. It is designed to carry a lighter fly (by Spey standards) and make a delicate presentation. It feels much like a traditional line when casting. It is light and crisp and will reward a short clean stroke with a tight efficient loop.

Some Scandi heads incorporate their own tips while others are meant to be combined with accessory tips. In my opinion, Scandi heads are great for those new to Spey casting. Their applications may be limited, especially for winter steelheading but they feel more like casting a traditional line and these heads require a cleaner stroke so they reinforce good casting habits.

Scandi heads are great for swinging shallow wet flies or skating dries for summer steelhead. Combined with floating running line there are lots of possible trout applications and although I’ve never tried it, my gut tells me they would be great with a popper on a little bass pond. I know guys who use them for smallmouth as well.

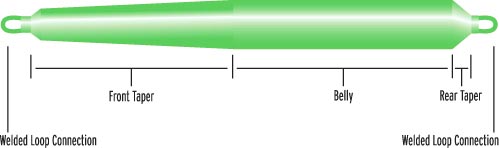

A skagit head, on the other hand, is designed for raw power. Its brutish belly and heavy front taper, which tapers very little, has the inertia to carry a heavy sink tip and a big fly on a windy day. It was designed to dredge deep runs on big rivers for winter steelhead and salmon. It’s a remarkable set up for that purpose but it is limited to this style of fishing.

The sink tip is an integral part of the skagit system. It serves two purposes. Obviously it is meant to carry the fly to the depth of the fish. The beauty of the system is the versatility of the interchangeable tips. Tips are available in a plethora of options from slow sinking clear intermediate to heavy full sinking tips like T17 and RIO’s MOW tips that combine a floating section with a sinking section in various lengths and sink rates. The angler is free to make their own tips of custom length and sink rates so the options are limitless.

The other purpose of the sink tip is much like that of the front taper. It dissipates the immense energy of the skagit head keeping the cast controllable. Unlike the Scandi head, you never fish a Skagit head without a tip. Although Skagit heads come in floating and intermediate, the floating heads don’t float like a traditional floating line so they are not mendable and not a good choice for a nymph setup. They are for swinging flies or stripping streamers. They have no top water application.

The component that is common to both Scandi and Skagit setups is the running line. This hundred foot or so section serves the same purpose as the section of a traditional line that shares its name. It connects the head, whether Scandi or Skagit, to the backing. This does not mean however that all running line is the same. There are three basic options. Coated, much like a traditional line, a coated monofilament core. Floating coated, a coated line that is mendable. Monofilament, this can be straight up big game 50lb mono or high tech mono made for the job.

For applications where mending your running line is not required, like swinging flies for steelhead, my favorite running line is RIO Slick Shooter. It’s a monofilament line with a super slick surface and an oval profile. It has very little guide or wind resistance and shoots for a mile. If you are likely to be fishing dry flies or nymphs at long distance, floating running line is a better choice.

Picture a skagit system with a short leader, a sink tip, the Skagit head and running line connected to the backing. You have all the same parts of a traditional line in the same order. The only difference is that you have the ability to change your line to suit the current conditions. Pretty cool, and I hope, less intimidating now that you understand it.

Now that we have covered traditional and Spey lines we should talk for a minute about switch lines. A switch line is a kind of hybrid. A chimera of traditional and Spey lines. It is a one piece line and, in fact, really is a traditional line but its taper is designed for Spey casting as well as overhead single hand casting. It’s not perfect for either but pretty good for both. It is designed to be an all around line for your switch rod and not a bad choice. For fishing nymphs under an indicator, it’s probably the best choice.

Understanding how lines and line tapers work is an important first step in choosing a line for your switch rod. Hopefully this information will help demystify the mechanics of the different types of line. In part two we will talk about choosing a line that works for you and your switch rod. In part three I will review a couple of lines that I use. Stay tuned and we’ll have you putting a bend in that switch rod before you know it.

Louis Cahill Gink & Gasoline www.ginkandgasoline.com hookups@ginkandgasoline.com Sign Up For Our Weekly Newsletter!

Sorry, but I don’t get the idea of a “switch rod” being something new. My two western steelhead rods are old, but they both have a four inch cork “fighting butt” that is “gripable” without a problem. Doesn’t that make them switch rods?

The main difference between Switch and Spey rods involves their overall length.

Spey rods, on average, are 12’6″ to 14’6″ (and more) in length.

Switch rods are 10’6″ to 12’5″ in length.

R.B. Meiser is credited with building and designing the first Switch rods in the mid 1970s. Here is a link to a very good article written by Mr. Meiser which makes for an interesting read.

And now the link…

http://www.meiserflyrods.com/switch-rods-info.php

It is my understanding that length doesn’t necessarily dictate whether a rod is switch or spey. There are shorter spey rods, like the 11′ 6wt Winston I use, that are not built to do anything BUT two handed style casting. Sure, it is 11′ but it is not a switch rod made to do a little bit of everything. I could be wrong but labeling a rod spey or switch purely on length is not what I learned to be correct. Maybe that was the way of thinking prior to the regular use of shorter spey rods, more of a modern way of looking at it? Thoughts?

All I know is that if I was fishing along a pool on the North Umpqua in Oregon and could back cast, I did. But, if a wall of willows was three feet off the water behind me, I could grab the fighting butt with my off hand and make a spey cast with no line going behind me. Maybe a little bit further along, back to normal casting. Isn’t that “switching?”

That’s an awesome river, got to fish it for the first time in September. Sounds like “switching” to me! My comment/question was more directed towards the differences in the construction between the two types of rods. Something I’m not very knowledgeable about.

Please clarify for your readers that lines for single hand rods utilize a different standard than those for two handed rods. For many individuals getting into two handed casting whether Spey or Switch, their understanding is that the two industry standards are the same. For that matter, the rod sizing and the weight lines/heads that they carry are not the same in both worlds. Within the past year, a friend of mine purchased a #8 Switch rod thinking that it was the equivalent of an 8-weight in the singled handed world. The rod purchase, due to his lack of understanding the difference, does not fit the intended purpose for which it was purchased. Now the rod sits un-used in a closet.

I would add there is a difference between short Spey rod and a true switch

But that spot Jeff is at… beauty for skating